In a little log cabin in rural Sumter County, South Carolina, at twelve o’clock noon, May 10, 1875, Mary McLeod Bethune was midwifed into the world and given the name Mary Jane McLeod. She was the 15th and first freeborn child among 17 siblings, and she was destined to make the most of her freedom.

Among her siblings and many other children in the village of her upbringing, Bethune was selected to attend a Presbyterian mission school in the nearby town of Mayesville. Later she wrote: “God helped me then, by sending into our little community the Presbyterian missionary, who came to the little village school and taught me to read the Bible.… I promised that if God would open up to me the wonderful messages of this book, I would teach my family and all who would come in contact with me to know them, and to understand them and try to live by them.” [1] It was with the learning acquired at this Presbyterian school that Bethune first demonstrated the missionary spirit that later led her to Moody Bible Institute.

A similar opportunity for Bethune occurred when she was selected by her Mayesville schoolteacher to receive a faraway benefactor’s scholarship to attend Scotia Seminary, in Concord, North Carolina. After some years at Scotia, she applied to and in 1894 was admitted to Moody Bible Institute in answer to her application letter, saying: “It is my purpose and my greatest desire to enter your Institute for the purpose of receiving Biblical training in order that I may be fully prepared for the great work which I trust I may be called to do in dark Africa.” [2]

Bethune first dreamed of being a missionary specifically in Africa when as a little girl she accompanied her father on a mule-and-cart trip to Mayesville to sell the family’s harvested cotton. There she met with an older sister with whom she went to the Methodist Church to hear a lecture by a celebrated African American professor named Dr. J. W. E. Bowen. Holding a PhD from Boston University and teaching at Gammon Theological Seminary, the Methodist seminary for blacks in Atlanta, Bowen was in Mayesville to lecture on missions in Africa. Remembering the occasion, Bethune wrote: “As I heard him tell about African people and the need of missionaries, there grew in my soul the determination to go some day and it has never ceased, and I sent up a prayer to God to give me the light, to show me the way that I, in turn, might show others.” [3]

With this yearning to be a missionary in Africa nurtured during her Scotia years, Bethune entered Moody for missionary training. Her hands-on experiences included setting up Sunday schools in neglected areas of Chicago, working among prisoners in the city jails, and helping at the Pacific Garden Mission. Located in a storefront in a demoralized section of town, the Pacific Garden Mission operated 24 hours a day, accommodating as many as 200 drop-ins with food, coffee, a bath, and clean clothing. Through these experiences, Bethune yearned to be a “fisherman of men” who could direct people into the “path of right living.” [4]

Then Bethune experienced a spiritual breakthrough at Moody. One evening Dwight Moody called the students into the Institute’s great assembly room and asked who among them felt the need for baptism of the Spirit. The purpose of this earnest desire was to be Spirit-empowered for service in the Great Commission for God’s glory. Recollecting the joy she felt, Bethune wrote: “I was so happy. I was there and could kneel in that great presence with open heart and mind awaiting the realization within my own life and the baptism of the Holy Spirit of the service.” [5]

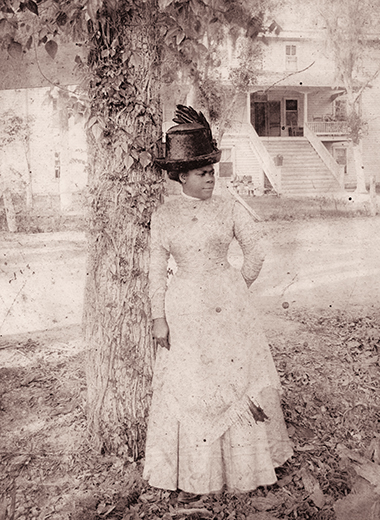

Two portraits of Bethune in her early years, about 1904.

Bethune’s missionary spirit was evident not only in the mission work she did while at Moody but in the way she conducted herself with her classmates. The only black student at the Institute, she was not only an anomaly but, for her roommate named Anna, “quite a study.” Bethune had a different texture of hair that Anna wanted to touch and brush, and Anna found the soles of her feet to be of particular interest: “Oh, Mary, I didn’t know that colored people were fair on the bottom of their feet. Why is the bottom different from the rest of them?” Bethune went on to develop a lasting friendship with Anna, recalling, “With no chip on my shoulder but as a student with an open mind I entered and was received by all most graciously.” [6]

Another instance of Bethune’s openhearted spirit suiting her to a life of missions occurred when Dwight Moody organized a “gospel car” and included Bethune among the five students sent to the rural districts of the Dakotas to establish Sunday schools. On one of her solo house-stops, Bethune told a story to the household’s little girls. When lunch was ready their mother said to her: “Miss McLeod, will you come to lunch?” The older daughter looked at Bethune and then at her mother and said, “Oh, Mother, let the lady wash her face and hands, they are dirty.”

Bethune was hardly the person easily offended and recollected: “The mother was embarrassed, but it did not embarrass me.” [7]

After completing two years of training at Moody, Bethune applied to the Presbyterian Board of Missions in New York for a chance to go to Africa. The Presbyterian Missions Board denied her request and instead sent her to Haines Institute in Augusta, Georgia. At Haines, a girl’s school founded by an African American named Lucy Laney, Bethune made use of the missionary skill and zeal she’d anticipated applying in Africa. [8] After a year at Haines, she taught in Sumter, South Carolina, where she met and married fellow teacher Albert Bethune, with whom she moved to Savannah, Georgia, and bore her only child. From Savannah, Bethune and family went to Palatka, Florida, where she taught children at another school supported by the Presbyterian Church. While in Palatka, upon hearing of the horrible conditions in which Negroes in Daytona Beach lived, Bethune set out on a tour of investigation that led to her founding the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute for Girls in 1903. This was the start of the institution that eventually became the renowned Bethune-Cookman College, later University.

Bethune with Bible, leading her Daytona Beach girls‘ school in 1905.

Over her years serving as president of her college and interacting with some of its students from West Africa, and also having mission experiences that took her briefly to Haiti and Liberia, Bethune relinquished her traditional view of missions as one-way service. Her matured view saw missions as two-way reciprocation in consideration of the “rich values to be gained from interchange between countries through visitation.” [9]

The ground of Bethune’s growth in the mission spirit began with her parents and her early upbringing. Undeniable however is the profound influence of her training at Moody Bible Institute and the lecture she never forgot Dwight Moody giving on power and its attainment: “Perhaps this was a part of the apex or the highest point of my religious life,” she recalled. “For I believe that this lecture, solidified with my whole period of training at Moody Institute, has had a profound influence upon my life and teaching.” [10]

Notes

[1] Manuscript titled “How God Has Helped Me,” undated, p. 1. Mary McLeod Bethune (MMB) Papers, Archives, Bethune-Cookman University.

[2] Rackham Holt, Mary McLeod Bethune: A Biography, New York: Doubleday, 1964, p. 40.

[3] Untitled interview beginning “I have been trying to analyze those qualities,” undated, pp. 16-17, MMB Papers.

[4] Untitled notes from Bethune to Rackham Holt, 1952, pp. 1-2, MMB Papers.

[5] Untitled manuscript beginning “After I completed my work at Scotia, undated, pp. 4-5, MMB Papers.

[6] Untitled notes from Bethune to Holt, 1952, p. 1. “After I completed my work at Scotia,” p. 3.

[7] “After I completed my work at Scotia,” pp. 3-4.

[8] Manuscript titled “A Yearning and Longing Appeased,” undated, pp. 2, 7, MMB Papers.

[9] Untitled manuscript beginning “This is a great historic honor,” June 20, 1946, p. 2, MMB Papers.

[10] “A Yearning and Longing Appeased,” p. 6.